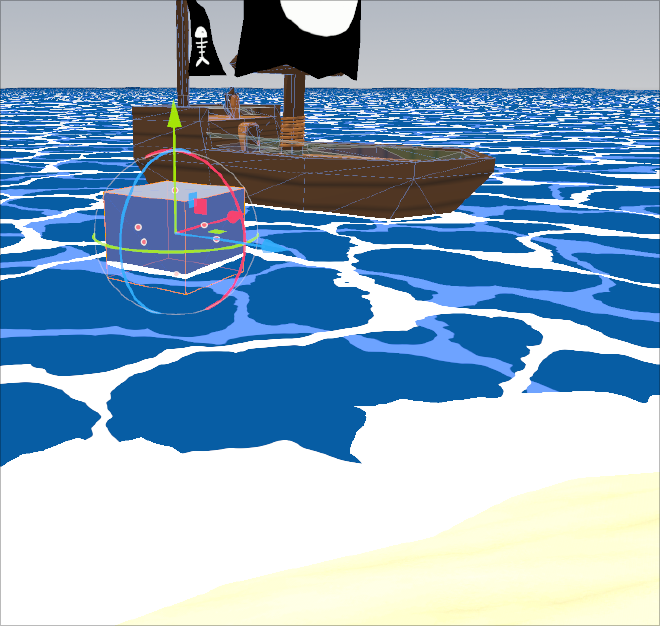

During the intro to a game I (perodically) work on, the player starts on a pirate ship. Realistic water doesn’t fit the style, and scroling textures on a big plane looked pretty boring. To make things a bit angrier I needed intense waves, and I needed those waved to actually affect the world.

Waves#

To keep it simple, we’ll just do a procedural heightmap; i.e. set the vertical coorinate to be a function of the horizontal position and time.

Sum of sines can add some semi-realistic texture to the surface of the water. I’m not doing that, but I am taking the basic idea of adding two waves with different frequencies to break up the repetitiveness.

float wave(vec3 p) {

float time = TIME * wave_speed;

vec2 uv = (p.xz + time * vec2(0.5, 0.5)) * wave_size;

float dist = length(uv);

return pow(2.1231, sin(dist) + sin((uv.y + 1.0))) * height;

}

void vertex() {

world_position = (MODEL_MATRIX * vec4(VERTEX, 1.0)).xyz;

VERTEX.y = wave(world_position);

}

Floating#

The fun part is making the waves interactive. There are two components to making objects float on top of our waves:

- Position: move the object up and down so it sits on top of the water.

- Rotation: orient the object according to the slope of the waves.

We generally want some of the object to sit beneath the surface of the water. There are more realistic buoyancy simulations that figure out the displacement according to the amount of a volume that sits beneath the surface. The complexity and noise that comes with an accurate solution doesn’t fit the style, so instead we’re going to fit a plane to the waves surface.

It’s easy to adjust the plane within the Godot editor, without doing anything custom, by defining a CSGBox3D that is thrown away at runtime.

Orientation#

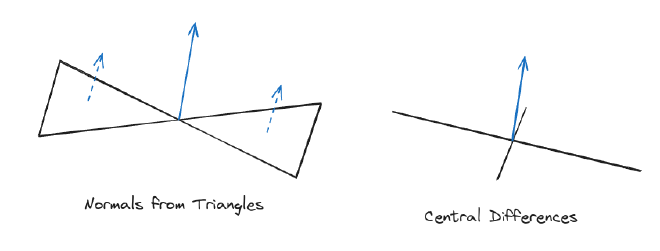

The easiest way to orient the object is find the slope of the wave using basic “rise over run”; aka finite differences with a small step.

var small_dx = _wave(center + Vector3.RIGHT * step / 2) - _wave(center + Vector3.LEFT * step / 2)

var small_dz = _wave(center + Vector3.BACK * step / 2) - _wave(center + Vector3.FORWARD * step / 2)

var gradient = (Vector3(small_dx, 0.0, small_dz) / step).normalized()

If the surface of our wave is very noisy, this will look pretty bad. A quick fix would be sampling at the edges of the plane that makes up our object’s “floating surface”. This would be “central differences”.

# find points on each side (the rotation puts us into global space, needed by _wave)

var left = _wave(center + (Vector3.LEFT * size.x / 2).rotated(Vector3.UP, plane.global_rotation.y))

var right = _wave(center + (Vector3.RIGHT * size.x / 2).rotated(Vector3.UP, plane.global_rotation.y))

var front = _wave(center + (Vector3.FORWARD * size.y / 2).rotated(Vector3.UP, plane.global_rotation.y))

var back = _wave(center + (Vector3.BACK * size.y / 2).rotated(Vector3.UP, plane.global_rotation.y))

var gradient = Vector3((left - right) / size.x, 1.0 , (front - back) / size.y).normalized()

Central differences will use a diamond shaped sample of points. Taking the corners into account, the normals can be calculated by looking at the triangles that make up our quad. In this example, I only use front and back triangles because I assume the shape of my rectangle is longer on that axis.

# find the corners (the rotation puts us into global space, needed by _wave)

# Define corners in local space

var local_corners = [

Vector3( half_x, 0, half_z), Vector3(-half_x, 0, half_z), # front

Vector3(-half_x, 0, -half_z), Vector3( half_x, 0, -half_z), # back

]

# Rotate and add to center (global space), then apply wave

for i in range(local_corners.size()):

local_corners[i] = center + local_corners[i].rotated(Vector3.UP, rot_y)

local_corners[i].y = _wave(local_corners[i])

# Also project center on the wave

center.y = _wave(center)

# Compute the two triangle normals

var normal_f = (local_corners[1] - center).cross(local_corners[0] - center).normalized()

var normal_b = (local_corners[3] - center).cross(local_corners[2] - center).normalized()

# Average the normals, then undo the global space rotation

var normal = ((normal_f + normal_b) * 0.5).rotated(Vector3.UP, -rot_y).normalized()

From left to right are examples using the back normal, the averaged normals and the front normal on top of a sharp peak.

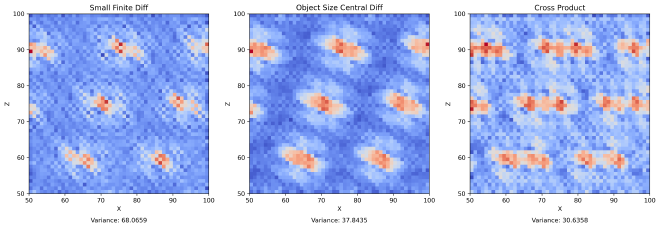

To be scientific about it, I plotted a “smoothness” field, the gradient of the computed normal-field. Not very surprising, sampling a bigger area results in smoother changes. The cross-product approach had the lowest variance, and spreads the variance around a larger space.

Position#

A naive position.y = wave(position.xy) means that at concave parts of the curve,

our plane will undernath the surface.

If we instead use the mean of our samples, we fix the concave case but now

we’ll end up submerged in convex areas. To get the best of both, we just take

the max of the center sample or the edge samples’ mean

(desmos).

# for central differences, re-use the samples

surface_point.y = max(center.y, (left + right + front + back) / 4)

# or if we're doing triangles, re-use those samples

surface_point.y = max(center.y, (front_l + front_r + back_l + back_r) / 4)

Riding the Waves#

Just for fun, I took things a step further and actually used the waves to drive the motion of the boat. While this may or may for the gameplay to move the boat around, it could be a cool effect for objects that fall into the water.

While I could find the partial derivatives of our wave analytically, I’d have to deal with that each time I change the structure of it. The normals and the gradient are closely related. In fact, when using finite differences, we’ve already computed the gradient.

func fit_plane(plane: Node3D, size: Vector2) -> Transform3D:

# ...

var step = .2

var small_dx = _wave(center + Vector3.RIGHT * step / 2) - _wave(center + Vector3.LEFT * step / 2)

var small_dz = _wave(center + Vector3.BACK * step / 2) - _wave(center + Vector3.FORWARD * step / 2)

var grad = (Vector3(small_dx, 0.0, small_dz) / step).normalized()

var surface_point = center - grad

# ...

Simply setting the object’s position to the surface_point like this it will

slide towards a local minimum of the wave and get stuck there. When we use a

smaller step we lag behind the wave, so the gradient at the point of the boat

changes over time. This results in a nice swaying effect.

Swimming#

What about objects that aren’t always in the water? We can re-use all of what we’ve done so far to implement a swimming mechanic. Instead of the model being a child of the plane, we can have a plane that is the child of a body.

First we detect whether or not we’re in the water to turn the influence on or off:

# get swimming position of the parent body

var surface_pos = water.fit_plane(self, Math.vec2(size))

surface_pos.origin -= (global_position - parent.global_position)

# activate swimming mode if we're submerged

if surface_pos.origin.y > global_position.y:

active = true

animation.queue_action("swim")

# if the player jumps or otherwise ends up above the surface, we're no longer swimming

if parent.global_position.y - surface_pos.origin.y > deactivate_margin:

active = false

And then apply the influence of the water on the body to velocity rather than directly

changing the position.

# align to surface

parent.global_position.y = surface_pos.origin.y

# push the player around with the waves

parent.velocity += (surface_pos.origin - parent.global_position) * delta

This bobbing effect looks neat. After some fine tuning, it could be pretty good, but there is already a lot of motion applied to the player outside their control. Another layer of unpredicatability would take away from the fun, so instead, lets make them stick to the water’s surface.

parent.velocity += (surface_pos.origin - parent.global_position) * Vector3(1, 0, 1) * delta

parent.global_position.y = surface_pos.origin.y

Well, setting the position directly means move_and_slide doesn’t get the

opportunity to slide the player and leads to them clipping through walls.

Instead, we can assign the y component of velocity so that it puts us exactly

on the surface.

var impulse = (surface_pos.origin - parent.global_position) * Vector3(delta, 1/delta, delta)

parent.velocity += impulse

parent.velocity.y = impulse.y

What’s next#

- Make some levels with this!

- Swimming/water levels. Diving?

- Make it so you can drive the ship.

- Taking advantage of the waves to gain some height could be a game mechanic.

- A better surface shader, that uses depth and a bit of transparency.

Foam.I made foam!